Fantasies

With an essay by Lynne Tillman

Damianieditore.com

2008

$45

Available for purchase at artbook.com .

See also the review by 5B4.

Excerpt

Lisa Kereszi, Mental Pictures

Children endure scores of prohibitions, and, to them, everything fun seems off-limits—staying up late, sex, alcohol, drugs, smoking. They refuse to go to bed, not wanting to miss anything, and long for the day when they will be free to do what grown ups do. Utterly enticing, the other side beckons. Its imaginary border will be transgressed as soon as the children can drive a car or stay out after 11 pm. Quickly, transgression itself becomes etched as a motif in the adult psyche.

How a child has pictured the hidden adult world will inhabit and shape the adult-child’s imagination forever. Many artists find their sources, not surprisingly, in memories of their pasts, actual and embroidered, and the results can function as resources for others, not only aesthetically but also as agents provocateurs for others’ buried sensations and memories. Lisa Kereszi’s photographs of off-hours scenes in sex clubs and the women who strip on their stages represent spaces for the unraveling of unspoken wishes and desires. Her images mark events, people, and places whose viewing was formerly prohibited, encouraging the formation of normal and highly ingenious fantasy lives.

A first transgression might be to visit a sex club like Show World, to engage in off-limits behavior and scenes. Kereszi’s witty take on this phenomenon is “No Cameras sign,” Show World, Times Square, 2000,” an image of the double-entendre sign, Ca[m]era or Picture Taking Not A[L]LOWED, in its club context. The prohibition against picture-taking is attached to a wall mirror that reflects, in a dizzying visual cacophany, the wild patterns, colors, planes, and angles of the club’s floor and ceiling. Disobeying the rule, her transgression, Kereszi shoots the conditions she finds there, a confusing space whose psychological effects are designed by the club, constructed formally just as her photograph is. Kereszi uses the mirror to conflate ceiling with floor, turning things upside down, topsy turvy, the way things are in a strip club: women undressing in front of strangers, promising sex, pleasure, anonymously. No pictures allowed, absolutely, because what happens there stays there, as in Las Vegas casinos whose carpeting is also designed to confuse and bedazzle. These places, the decor insists, are not home, but unheimlich, uncaany and strange, and you can be strange here, too.

In Kereszi’s “poses,” her visual points of view, she offers up the human fascination with sex, sexuality, and the female body. Her images supply and deny desire or libidinal feelings, since she stages erotic events both to seduce and distance the viewer, to entice and interrogate our interest in them. While Kereszi’s work may defy a viewer’s expectations, interrupting a revery, it also identifies the persistence of illusion and wish. With this ambivalence toward what she photographs, Kereszi acknowledges that no picture can satisfy desire; more likely, it will embolden it. Wanting more, the viewer looks harder, deeper.

Her images respond by teasing the furtive, hungry imagination. In “Sex Shop Curtain I, Pigalle, Paris 2001,” a dark red or maroon velvet curtain hangs across an entrance, with one drape drawn back, beckoning a passer-by to come in. The lush curtain falls between soft-green old-seeming plaster walls, its color reminiscent of paintings by Toulouse Lautrec. The image includes the floor and rises to the height of a person’s waist, the perspective angled from above and one side. In an actual space, a passer-by might look up first, to find the top, but then peek through the parted curtains, past the facade to the inside. It’s an unsettling position for a spectator, because from this perspective it appears that one sees, but with no head and eyes. Kereszi turns curiosity into a thing of of the mind, incorporeal; and, headless, heedless, people plunge forward, ignorant of what awaits them on the other side. A picture such as this proffers the existence of a greater conundrum outside its frame, in the viewer’s mental life.

The exotic dancers, strippers, and burlesque queens, sitting or performing before Kereszi’s camera, are mutable subjects whose identities are constituted, in part, by the eye of the beholder. In some photographs, they wear fetishistic costumes, meant to be stripped off. In others, the women strike poses, acting as models of sensuality. They prance before the crowd seductively, portraying sex and lust as delightful and easy, and they appear to enjoy it. This radiates in “Dirty Martini’s Legs, Women Watching, NYC 2003,” in which Dirty Martini is shot from her legs down, a swirling yellow feather boa whipping around her. At the edge of the stage, three women gaze raptly, resting their arms or hands on the floor at her feet. A man stands behind the three women, looking up, his expression obscured; the rest of the crowd is in darkness. Their absorption embellishes the picture with spectatorial enjoyment, wariness, bemusement, surprise, and they also stand in for the picture-viewer. Arrestingly, in this body of work, women watch other women strip, a decision that highlights Kereszi’s emphasis on the complexity of looking: women, heterosexual or homosexual, are as voyeuristic as men, excited by looking at women, too.

Comparing “Dirty Martini’s Legs, Women Watching,” with “Dirty Martini’s Legs, with Feather Fan, NYC 2001” allows close consideration of Kereszi’s compositions by which she induces different shades of meaning. The absence of an audience, in the latter photograph, is striking. Shooting from behind, Kereszi focuses on Dirty Martini’s meaty, marbled legs and Rubens-esque bottom, a yellow feather boa floating in the air as if another of her appendages. Dirty Martini is alone, onstage, in action, and one sees her truncated body, imagining her whole, perhaps, her breasts and belly, and, without others gazing at her within the frame, one is also alone, identifying more, possibly, with the dancer, her position in the moment. What happens then? How does gender effect looking, if it does, and in what way? Is it more or less comfortable in this spectatorial position, without the cover of others through whom one can look? And if one “becomes” Dirty Martini, what is the viewer’s experience of her existential condition?

Kereszi hopes to provoke and plunder our human curiosity and mostly presents partial views of strippers, their backs, thighs, forelegs projecting from a swing, as they stand in shadow or perform at a distance. Her images foster an urge for fuller exposure, for everything to be revealed, and a spectator of the show or the photograph might hope that, by this stripping away, the mystery of sex, sexuality, and women might be solved. But what is revealed, rather, are more questions about the inexplicability of human desire, its immunity to discovery, and the relationship of so-called daily life with fantasy life.

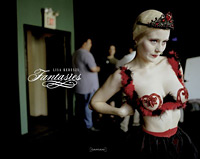

At home and in their dressing rooms, the women are images in the act of transforming themselves into other images. They love their cats, change their shoes from flats to spikes, have trouble with their zippers. They have imperfect bodies, some quite overweight, but in Kereszi’s pictures, the women appear uninhibited by their fleshiness; they display and use it with pleasure. Backstage, as the strippers don their paraphernalia and apply make up, their similarity to ordinary women is inescapable. Kereszi’s character studies resonate with the women’s candor, registering another idea of nakedness: Unguardedness reveals or suggests character and psychology, nudity only a body.

In “World Famous Bob sitting on her bed, Brooklyn, 2003,” a blond-haired, fresh faced woman, with large breasts encased in a pink bra, poses for the camera atop a plush pink bedcover the color of her bra and panties. Bob is like a big doll with a pale pink bow tied atop her head, a white and pink heartshaped pillow near one arm, to the left of her. To the right, her costumes hang from a metal rod. Her abundant breasts, spilling out of her bra, are dead center in the frame. In this context, Bob projects innocence, despite extra long fake eyelashes and a scanty costume. But who is she? The girl next door, a contemporary Mona Lisa, a satyr, an exhibitionist, a demure woman making a living for her kids, a shy sentimentalist, or a cynical Romantic? Perhaps all of these, or none. “World Famous Bob at home” counters her stage image, and, by juxtapositions such as this, Kereszi wrestles with the antique dualistic conception of women, Madonna or whore.

Kereszi portrays sex clubs the way she does her female characters: they are not inherently fantastic, only places. The clubs are presented in various stages of “undress,” before and after shows, stripped of mystery. Without spotlights, smoke and mirrors, the clubs are shown to be constructed fantasy spaces. A club’s lockers remind one that the women go to work, undress, dress, and go home, and, undecorated, the clubs look bleak, without glamour, or the whiff of excitement and danger that transgression supplies. These dingy rooms promise nothing. Kerezszi suggests that magic, illusion, is necessary to elicit fantasies, but also that the imagination needs little to flourish, only a few props: low lighting, flashing lights, something called atmosphere. These essentials are not that different from the practice of photography, the illusions it creates and the apparatus it requires to make a picture effective.

In Kereszi’s “Pink carpet steps at strip club, Bourbon Street, New Orleans, 2000,” the club wears pink, like World Famous Bob. Central in its frame, a silver pole at the front of a stage cuts the picture into perfect halves, while the stage itself divides the picture plane horizontally. The pink-carpeted steps ascend or descend to the stage, to the pole. Barstools set upside down on the stage send the eye to the ceiling, which is painted pink. On the left side of the picture, an upside down chair leg parallels the line of the silver pole, on and around which dancers perform. The eye travels to the back of the room, to its horizon line and illusionary deep space, but the pole intrudes. Still, the pink stairs, like parted pink lips, suggestively lead the way up and in. Here, Kereszi plays with both the flatness of a photograph and the persistence of illusion, the photographs’s and the viewer’s. As in “No Cameras sign, Show World, Times Square, 2000” and others of Kereszi’s before-and-after club photographs, she emphasizes the space’s colors, planes and angles, its architecture. In “Pink carpet steps,” the chairs and pole stand in for the absent customers and pole dancers. Viewers must work to see its usual fare, its phantasmagoria.

Night clubs and strippers are not unique photographic subjects, but Kereszi’s approach to them is. She frames and presents the not-homey and unfamiliar, but brings the characters and places out of territory often named obscene, or that which is meant to be kept out of sight. She brings them out of the dark, often literally. What is usually underlit is overlit. What is usually exposed is clothed or not ready for exposure. What should be glamorous is plain. What should be other is familiar. Each of her images considers persons and contexts, as well as the viewer who conjures many more pictures than any one artist could think up.

Photographs, like strippers and sex clubs, are constructed spaces that rely on illusion. Viewers animate pictures, flat pieces of paper, with meanings and interpretations. Lisa Kereszi and her teachers and mentors, Stephen Shore, Phillip-Lorca DiCorcia, Nan Goldin, Tod Papageorge, Larry Fink, Laura Letinsky, Dana Hoey, Gregory Crewdson, render objects on which people project subterranean hopes and wishes. Their art represents places and people that multiply, in millions of minds, millions of confabulations, because what does not appear in these pictures also engenders images.

Lisa Kereszi’s lush, poignant, frank, beautifully composed image-world reminds one that what is included in, or excluded from, the frame is not just a formal matter. The paradox of her photographs is that they both reward the need to look, and, at the same time, create cravings for more, to see manufactured what can never be pictured, the fantasies of childhood.

Copyright Lynne Tillman 2007, Fantasies